Spotlight on Black Children, Youth, and Families

A legacy of racial injustice has led to inequities in access to protective, high-opportunity communities for Black children, youth, and families. Addressing these disparities demands intentional, research-informed efforts to expand access to resources that promote and protect their well-being. To contribute to such efforts, we reviewed a decade of research on PCRs, identifying key lessons and gaps related to Black children, youth, and families. We then conducted research with Black families and caregivers of children from birth to age 17 and with emerging adults ages 18 to 25 to understand their perceptions of and access to PCRs. In this section, we share key research findings, along with examples of initiatives that reflect some of these insights.

Research findings on PCRs for Black children and youth, 2012-2022

To summarize current knowledge within the field on PCRs for Black children and youth, we analyzed findings from 143 of the 172 studies included in our systematic literature review. These selected studies included Black participants from birth to age 24. Some studies focused primarily on Black children and youth, while others either conducted separate analyses by race or controlled for race. Key insights from our analysis are shared in the brief, “Black Children and Youth Can Benefit From Focused Research on Protective Community Resources,” with highlights provided below.

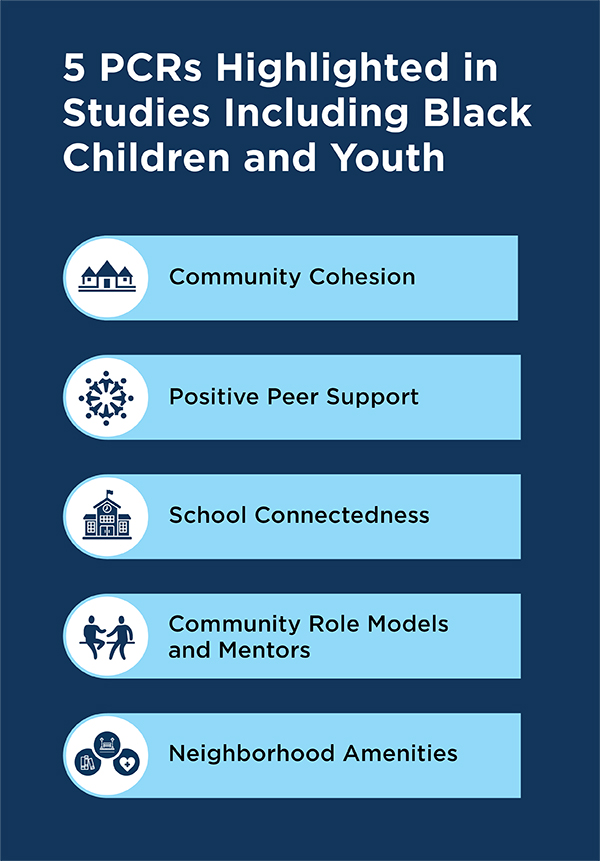

The studies highlight several PCRs associated with Black children and youth’s well-being. Five of the most frequently referenced PCRs include community cohesion, positive peer support, school connectedness, community role models and mentors, and neighborhood amenities and services.

Community cohesion, or the presence of close social relationships within a neighborhood, is linked to positive mental and behavioral health outcomes for Black children and youth who are exposed to risks such as economic hardship, discrimination, and violence.

Community cohesion, or the presence of close social relationships within a neighborhood, is linked to positive mental and behavioral health outcomes for Black children and youth who are exposed to risks such as economic hardship, discrimination, and violence.- Positive peer support is consistently associated with Black adolescents’ school attitudes, behaviors, and success, as well as their physical and mental health.

- School connectedness, including Black youth’s perceptions of positive school cultures and their relationships with staff, is positively associated with their educational goals and prosocial behavior.

- Community role models and mentors serve as protective resources for Black children and youth facing social, emotional, economic, or physical risks.

- Neighborhood amenities (e.g., sidewalks, recreation centers, libraries, green spaces, high-quality food stores) and services (e.g., medical and mental health providers) are crucial for Black child and adolescent health and safety.

Despite these findings, significant gaps in knowledge remain. These gaps arise from the limited representation of Black children and youth in research—including insufficient analysis by age, gender, sexual identity, and geographic location, as well as limited engagement of Black children and youth in the studies themselves. For example, there is a lack of research on PCRs for Black children under age 9 and a scarcity of studies focusing on Black LGBTQ+ youth. Additionally, most research on PCRs has focused on urban populations, with limited attention to those in rural areas. Existing studies have also been predominantly quantitative, with few qualitative studies offering deeper insights into the lived experiences of Black children and youth.

These gaps highlight critical areas for further inquiry. Group-specific and within-group analyses of PCRs for Black children and youth are essential to ensure that policies and interventions address their diverse needs. Furthermore, there is a pressing need to evaluate interventions that promote the positive development of Black children and youth. To fill these gaps, research must adopt more inclusive, community-engaged designs, ensuring that Black children and youth are not only included in studies but are also central to them.

Community mapping studies with Black families and emerging adults, 2024

To address some of the limitations identified in our analysis of research on PCRs involving Black children and youth (see previous section), we collaborated with the National Black Child Development Institute (NBCDI) and Cities United (CU) to conduct community mapping studies (a participatory method that focuses on community assets) on PCRs with Black families with children from birth to age 17 and with Black emerging adults ages 18 to 25, respectively. Through community mapping activities and focus group discussions with participants, we sought to document how they define and perceive PCRs and to identify the PCRs they have access to and those they desire but find largely inaccessible.

Community mapping studies with Black families

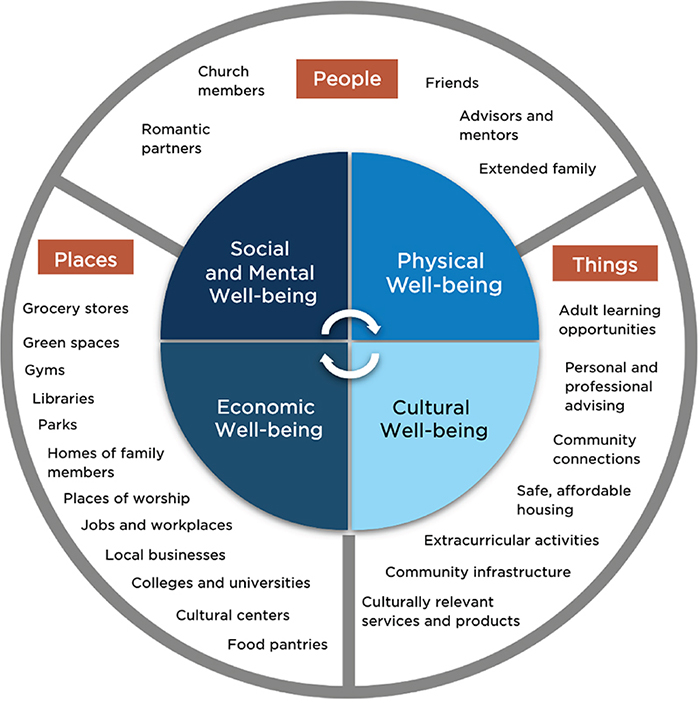

We collaborated with NBCDI to host in-person community mapping activities and focus group discussions with 44 Black parents and caregivers of children from birth to age 17. These sessions took place in March and April 2024 in eight cities in the four geographic regions of the United States: North (New York City, NY; Philadelphia, PA), South (Nashville, TN; Tampa, FL), West (Sacramento, CA; and Seattle, WA), and Midwest (Cleveland, OH; Detroit, MI). Participants described the distinct yet mutually reinforcing benefits provided by the protective people (e.g., family networks), places (e.g., recreational areas and green spaces), and things (e.g., advisement and extracurricular activities) in their communities (See Figure 1). These benefits were primarily centered around health, safety, and positive child and youth development.

Figure 1. PCRs identified by Black parents and caregivers of children from birth to age 17

Parents and caregivers also described risks associated with the absence of PCRs. For example, families without access to one or more of the identified protective places reported unmanaged health conditions and limited emotional and behavioral support. They also reported fewer opportunities for artistic development and positive racial identity formation. Finally, they described the inaccessibility of these spaces as a factor diminishing their opportunities to experience family togetherness and joy.

Community mapping studies with emerging adults

We partnered with CU in May and June 2024 to conduct virtual community mapping activities and focus group discussions with 12 emerging adults—seven women and five men—ranging from 18 to 25 years old. These participants discussed the people, places, and things in their communities that supported their well-being across four dimensions: social and mental, physical, economic, and cultural (See Figure 2). The findings of this study emphasize the critical role of PCRs in fostering a holistic sense of well-being among Black emerging adults.

Figure 2: PCRs and the well-being of Black emerging adults

For example, participants noted that romantic partners, family members’ homes, and advisors were supportive of their social and mental well-being, providing emotional security, comfort, and mentorship. Friends, grocery stores, and sports contributed to participants’ physical well-being by reinforcing their capacity to maintain a healthy lifestyle. In terms of their economic well-being, participants commonly named mentors, workplaces, and transportation as allowing them to maintain stable employment and manage their finances to meet both their immediate needs and long-term financial goals. Finally, participants’ cultural well-being was supported via church members, local businesses, and community connections, fostering a sense of identity and preserving cultural traditions.

Initiatives to build protective communities for Black children, youth, and families

Across the country, local and state initiatives are making a real impact on creating the safe, supportive, and hopeful environments that all families need to thrive. These efforts emphasize the power of community engagement and the importance of multi-sector collaboration to address the historical disinvestment in Black communities.

Here are a few examples:

- Minnesota’s Whole Family Systems Initiative: This collaboration between state agencies, local organizations, families, and communities focuses on supporting multi-generational family well-being. By prioritizing racial equity, the initiative works to preserve and strengthen families while expanding their social networks—connecting them to relationships that offer mutual benefit.

- Philadelphia’s Rebuild Initiative: Funded by a beverage tax, Rebuild is transforming the city’s parks, recreation centers, and libraries. With over $400 million invested, this initiative focuses on revitalizing neighborhoods that have suffered from years of neglect. It also creates workforce development opportunities, ensuring that underrepresented groups are involved in rebuilding the city’s infrastructure.

- Fairfield, Alabama’s Carver Jones Market: In response to a lack of healthy food options, Urban Hope Community Church and James Harris, a supermarket industry veteran, worked together to open the first grocery store in Fairfield offering fresh produce and meats in over a decade. This community-driven project addresses food insecurity and brings fresh, healthy choices to a predominantly Black community.

- Africatown Community Land Trust in Seattle: This initiative is helping to revitalize Seattle’s historically Black Central District through a community-led land trust. A collaboration of real estate professionals, business leaders, and residents, the Africatown Trust promotes business development, economic growth, and cultural preservation—ensuring that local communities benefit from the area’s revitalization.

More From Child Trends on PCRs for Black Children and Families

Click to continue to Section 2: Resources

View ResourcesSuggested Citation

Sanders, M., Martinez, D.N., Winston, J., & Rochester, S.E. (2025). A toolkit for using protective community resources to promote child, youth, and family well-being. Child Trends. DOI: 10.56417/2058t7973j

© Copyright 2025 ChildTrendsPrivacy Statement

Newsletter SignupLinkedInYouTubeBlueskyInstagram